Find It Locally

Search CISA’s online guide to local farms, food, and more!

Find Local FoodPrepared for Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture (CISA) by:

Ellen Dickenson, Spirit Joseph, and Jonathan Ward

Isenberg School of Management, University of Massachusetts Amherst

State funds for this project were matched with Federal funds under the Federal-State Marketing Improvement Program of the Agricultural Marketing Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Western Massachusetts meat producers use USDA-inspected slaughter and processing services located within reasonable travel time in Athol and Groton, Massachusetts, southern Vermont, and eastern New York. Other than the slaughterhouses, however, there are few, if any, businesses in our region that provide butchering, processing, and curing services to local meat producers. CISA initiated the research presented in this report to assess additional options for meat processing, with the goal of expanding the variety of local meat products available, giving producers a choice of services, and encouraging growth in local meat production.

We were very pleased to work with a research team of MBA students from the University of Massachusetts’ Isenberg School of Management. They chose this project from a number of options because of their interest in local foods businesses, in the Pioneer Valley region where they live, and in non-profit management. We are grateful for their excellent and thorough work, as well as the insight and experience provided by producers, processors, and buyers throughout the course of the research.

In response to this research, CISA has expanded our training opportunities for meat producers. We will continue to work with the Western Massachusetts Food Processing Center to support the addition of meat products to the list of products which can be prepared or processed in their shared-use kitchen. We expect that the regulatory and feasibility analyses contained in this report will be useful to entrepreneurs, meat producers, existing processors, and others who might start or expand a business related to meat processing or services that benefit meat producers.

We are very interested in your feedback and I invite you to send me your comments.

Margaret Christie,

Special Projects Director

This report aims to explain and provide recommendations to address challenges in commercial meat processing in the Pioneer Valley. Multiple conversations with meat producers, processors, and local food advocates in the area were conducted over the past three months, and a number of recurring themes emerged. Local producers expressed their concern with a lack of options available for creating and customizing value-added meat products in the area. Additionally, producers described a need for business and technical assistance, a shortage of data on demand for local meat products, excessive travel to and from processors, as well as problems with the quality of service received from existing processors. Many of these issues could be addressed by improving producer education, increasing the level of coordination among local producers in order to strengthen their collective bargaining power with processors, and reducing their operational costs, primarily related to transportation for slaughter and processing services.

These issues, however, are hardly confined to meat processors in the Pioneer Valley, being largely connected to apparent shortcomings in small-scale meat processing infrastructure across the country. To this end, current models for improving local meat processing options, as well as alleviating other business challenges faced by small producers, were identified elsewhere and considered for their applicability to the conditions in the Pioneer Valley.

All alternatives were considered for feasibility based on their ability to address current challenges faced by producers, impact on existing local commercial processing facilities, startup costs, and time to launch. Ultimately, three recommendations are proposed for implementation:

Moving forward, additional areas of research are suggested, such as a detailed analysis of demand for local meat products and processing services, an assessment of the consumer’s perspective of the local meat industry, and an investigation of the impact of labor issues on meat processors in the area and recommendations for addressing those challenges.

Click here to download the full PDF report, or use the links in the table of contents to navigate the HTML text.

Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture (CISA) strengthens local agriculture by building connections between farmers and the community. CISA’s strategic plan focuses upon four main strategies to achieve its mission:

In 2006 and 2007, CISA conducted an extensive study of the options and demand for slaughter and processing facilities for livestock raised in western Massachusetts.1 The study was driven in large part by the fact that two USDA inspected slaughterhouses had recently burned down, forcing many local meat producers to travel much greater distances to have their animals slaughtered. The study evaluated multiple options, including a new small-scale commercial slaughter and processing facility, a mobile slaughter and processing unit, a commercial meat processing facility without slaughter capability, upgrading an existing custom slaughterhouse to a USDA inspected commercial facility, or rebuilding a destroyed slaughter and processing facility. Fortunately, Adams Farm, one of the two slaughterhouses that had been destroyed, decided to rebuild a new 13,800 square foot slaughter and processing facility, which opened in 2008. Currently, livestock producers in western Massachusetts have access to two USDA inspected slaughter facilities in Massachusetts, in addition to several across the border in Vermont and New York.

While access to slaughter facilities has improved somewhat since 2007, a number of challenges still exist in the meat processing industry. Meat producers want additional options for product diversity, packaging, quality, and customer service. Bottlenecks and slowdowns at regional slaughterhouses often occur at the post-slaughter processing stage, and not at slaughter, so new cutting options could also improve scheduling flexibility. Therefore, this report aims to:

go to: table of contents | top of section

The history of agriculture in the United States has been a complex and remarkable story. According to the American Farm Bureau Federation, “today’s farmers produce 262 percent more food with two-percent fewer inputs (i.e. labor, seeds, feed, fertilizer, etc.), compared with 1950.”2 At the same time, the number of farms in the United States has steadily declined, from 6 million farms in 1940 to 2.2 million in 2002. During this time, the average farm size has nearly doubled and the average number of commodities grown per farm has declined to just over one.3 Thus, the overall picture of agriculture is one of increasingly consolidated, large-scale production of monoculture commodity crops. In fact, just “125,000 farms (out of 2,204,792 total) produce 75 percent of the value in U.S. agricultural production.”4 This trend has yielded tremendous benefit, as over the majority of the past 70 years, food has been plentiful and relatively low cost in the United States.

These gains, however, have not come without substantial trade-offs. Critics charge that the current agricultural system is largely unsustainable due to its reliance upon substantial fertilizer inputs, transportation requirements, and harmful waste products created. A growing movement, including farmers, consumers, and policy advocates, has promoted a system of agriculture much different from the large scale, mechanized system of food production. The alternative is based on a smaller-scale model, in which food is primarily produced and consumed locally. A number of benefits are realized through a local focus on agriculture. It lies beyond the scope of this report to fully describe all the benefits of local food; however, a few important factors include:

Local and regional food systems have been growing dramatically in recent years. According to the USDA, the number of farmers’ markets has more than doubled since 2004, rising nearly 10% from 2011 to 2012. Meanwhile, more than 12,000 CSAs6 were reported in the 2007 USDA Census of Agriculture, with their popularity continuing to rise. Beyond farmers’ markets and CSAs, it is increasingly common to find restaurants and grocery stores promoting meat and produce sourced from local producers. 18,467 more small farms were counted in the five years since 2002, with a growing ethnic, racial, and gender diversity amongst farm operators. In the Pioneer Valley, investment in local food has been a strong and prevalent trend, thanks in large part to the work of CISA and its partners over the past twenty years.

go to: table of contents | top of section

Meat production is a huge part of the U.S. agriculture sector, representing more than half the value of all agricultural products and “often exceeding $100 billion per year.”7 In 2011, the United States produced 110 million hogs and 34.1 million beef animals. Thus, meat production represents a substantial component of the economy.

Similar to the overall trends in agricultural production, meat processing has undergone dramatic consolidation over the past several decades. As of 2005, four companies controlled 83.5% of the beef cattle slaughtered in the United States, while four others controlled 64% of the hogs slaughtered.8 Even as the amount of red meat slaughtered has grown, consolidation in the industry has actually resulted in a decrease in the number of meat processing facilities. The number of USDA inspected slaughterhouses fell by 20% between 2002 and 2007.

Thus market forces in the meat industry, to a greater degree even than in agriculture at large, have moved to large-scale, high-volume production. Larger operations and more consolidated systems require a smaller number of large-scale meat processors. In contrast, a local or regionally focused food system requires a larger number of small-scale meat processors.

go to: table of contents | top of section

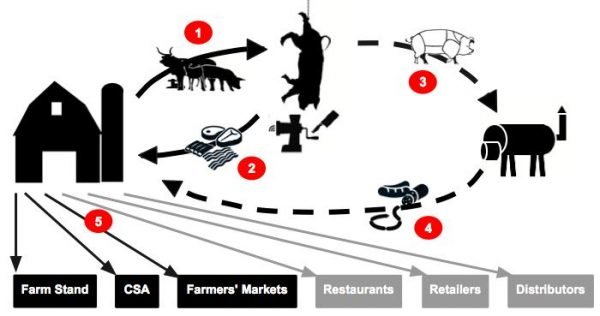

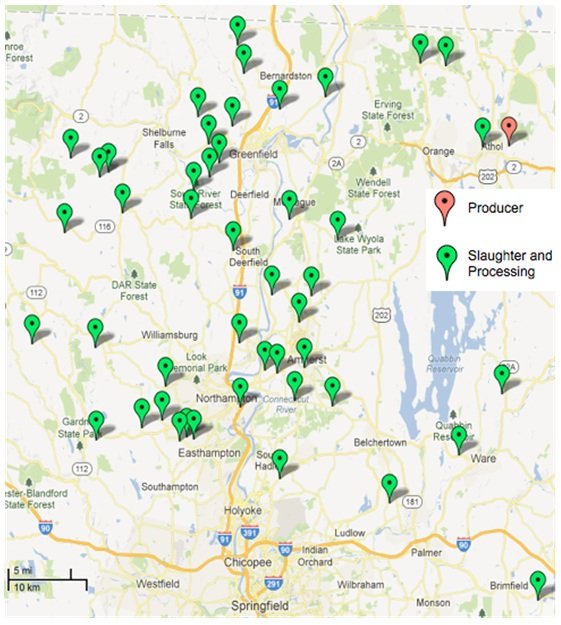

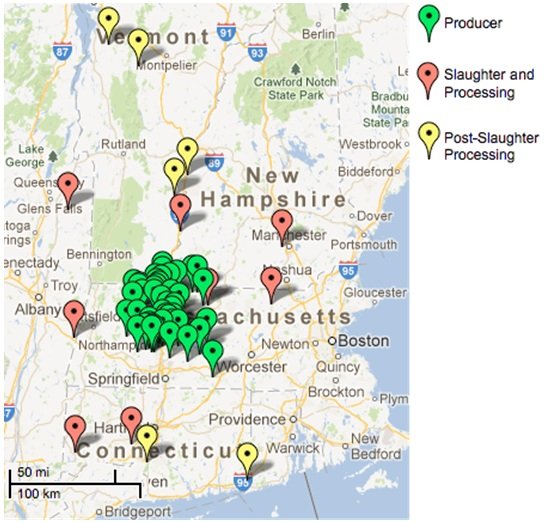

The meat industry in the Pioneer Valley is characterized by a cluster of at least 49 small commercial farms9 in Franklin, Hampshire, and Hampden counties, each with an average pasture area of 20 acres,10 with meat processors located outside the periphery. The most commonly raised livestock animals in this area are beef, sheep and lambs, hogs, and goats. Exhibit 1 depicts the typical process by which livestock is converted to meat and sold to end consumers in this area.

Exhibit 1: Local Meat Production in the Pioneer Valley

1) Producer delivers live animals to slaughter and processing facility. 2) Producer retrieves meat products from slaughter facility. 3) Some producers opt to bring their primal cuts of meat to a second processing facility in the region that is able to make a greater variety of value-added products than the slaughter facility. 4) Producers opting to use a second processing facility retrieve meat products. 5) Producer sells meat direct to consumers at the farm stand, CSA, and/or farmers’ markets. Many producers also opt to sell meat wholesale to local restaurants, grocery retailers, and distributors.

In Massachusetts, producers must have their livestock slaughtered and processed in a USDA inspected facility if they wish to sell the meat. There are only two USDA inspected slaughter facilities in Massachusetts—Adams Farm in Athol and Blood Farm in Groton. There are currently no USDA inspected meat processing facilities located in Franklin, Hampshire, or Hampden counties. Adams Farm, located in Worcester County, is the most popular facility among commercial meat producers in the Pioneer Valley. Adams and Blood Farm both provide cutting and other value-added processing services. A few custom slaughter facilities also exist in Massachusetts, although they are not able to kill and process livestock for resale, and therefore serve commercial meat producers, since the facilities are not inspected by the USDA.

A greater variety of slaughter and processing options are available in states surrounding Massachusetts, within a few hours’ drive of the cluster of livestock farms in the Pioneer Valley. The closest slaughter facilities to the area are Hilltown Pork in Canaan, New York and Westminster Meats in Westminster Station, Vermont. One producer in this study reported transporting his animals almost 100 miles away to Locust Grove Farm in Argyle, New York for processing.

In addition to slaughter facilities, there are several value-added processing options located outside of Massachusetts. These facilities do not provide slaughter services, but they will further process quarters and primal cuts. Many of these facilities are capable of making smaller batches of highly differentiated and even custom meat products for producers’ private labels, which draws some business from producers in the Pioneer Valley. One example of a value-added processing facility that is used by producers in western Massachusetts is Vermont and Green Mountain Smokehouse in Windsor, Vermont. For a map of the commercial meat processing industry described above and a list of key members of this value chain, please refer to Appendix II of this report.

After slaughter and processing, producers retrieve their meat, which is typically frozen, from the processing facility and bring it to market. Larger producers in the Pioneer Valley sell a portion of their meat wholesale to local restaurants and retail markets. All producers involved in this study earn some revenue from retail sales at their own farms. Many also sell their meat directly to consumers at farmers’ markets, as well as to their CSA members.

go to: table of contents | top of section

Meat is a highly regulated product in the U.S. out of concern for consumer safety, with production and sale of meat governed at the national level by the USDA. Some states, New Hampshire and Vermont for example, have their own regulations that govern in-state meat production and sales, the standards of which must be at least as high as those of the USDA. Although Massachusetts does not yet have its own body of regulations governing the production and sale of meat products, there is currently legislation pending to establish a state meat inspection program.11 Additionally, under the USDA’s new Cooperative Interstate Shipment Program, if a state inspection program was implemented in Massachusetts, select meat processors with less than 25 employees could apply for the ability to ship products they process across state lines, enhancing the economic viability of any new, small-scale slaughter and processing facilities launched in the area.

It is important for any party aspiring to establish a meat processing business to fully understand the USDA’s requirements for processing facility infrastructure, documentation, inspection, transportation, and labeling. Any processing business will require an approved facility, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) and Sanitation and Standard Operating Procedures (SSOP), and will be monitored by a USDA Inspector.

There are two exemptions under which meat can be processed in a non-USDA inspected facility: the retail exemption and the custom processing exemption.

Retail Exemption

The USDA FSIS Retail Exemption allows retailers, such as grocery stores, markets, and butcher shops, to engage in the processing and sale of any type of meat product, without mandatory USDA inspection, so long as the majority of these products are sold directly to household consumers. Essentially, the Retail Exemption exists for sales that are primarily made to household consumers, and the facility cannot sell products to other retailers for subsequent sales to consumers. A local producer, who might wish to have a butcher shop prepare various meat cuts and products for them in order to then sell those products at a local farmers’ market, is categorized as a retailer. Therefore, the meat products that they sell must be inspected by the USDA, and could not be produced by another business under the Retail Exemption.

Custom Exemption

The Custom Exemption allows for the slaughter and processing of livestock without USDA inspection so long as those animals are consumed solely by the owner’s household and non-paying guests. Livestock processed under the Custom Exemption must be labeled as “Not for Sale” and cannot be resold. Therefore, this exemption is not able to serve the processing needs of a commercial meat producer.

go to: table of contents | top of section

A total of 30 individuals involved with the meat processing industry in western Massachusetts and individuals who have developed robust local meat economies in other parts of the country were interviewed in order to produce this report. These interviewees are livestock producers, meat processors, retailers, restaurant owners, distributors, and food policy experts. These one-on-one interviews were conducted either in person or over the phone in order to gather in-depth information about the meat processing industry in the area, much of which would likely not have been communicated through a survey.

After completing this round of in-depth interviews, the investigators facilitated a focus group of livestock producers from the Pioneer Valley in order to clearly identify the most critical issues facing these stakeholders and rank them in order of importance. These rankings are based on the severity of each issue’s impact on producers’ businesses, as reported by the producers themselves.

Through primary research, six major issues, which are obstacles to the production and sale of local meat in the Pioneer Valley, were identified:

Each of these issues is described in detail below.

go to: table of contents | top of section

Business and Technical Assistance

It was revealed in the nominal focus group of Pioneer Valley meat producers that there is a need for readily available and affordable business assistance. This need is widespread, according to interviews with agricultural experts,12, 13 and a recent report from the Niche Meat Processor Assistance Network.14 Specific needs, in order of importance, include:

According to the producers in the focus group, this collection of issues has the greatest impact on individual farm businesses. Additional issues in this category, though not as critical as the six listed above, include the prohibitive cost of having a high-quality display in a farm’s retail space, as well as identifying a market for non-edible parts of animals such as the hide and horns.

Greater access to technical advice related to production and processing is also a necessity for meat producers in the Pioneer Valley, especially for those who are new to commercial livestock farming. Examples of technical assistance may include understanding how to use a processor’s cut sheet, the options available and inputs needed for various value-added products, and guidance relating to accessing certain claims and certifications, like grass-fed and organic.

Additionally, due to the seasonal nature of harvesting meat, it can be very difficult for meat producers to schedule slots for their animals at their processor of choice between September and December—the busiest time of year for meat processing. Most veteran producers try to schedule these appointments up to a year in advance in order to ensure that their animals will be accommodated. Often, they also try to bring animals to slaughter consistently throughout the year in order to reduce the strain on processors and smooth their own inventory. Scheduling slaughter and processing, however, can be a frustrating and costly experience for newer producers who are unaware of the need for advanced notice, sometimes requiring them to house and feed their animals for unanticipated periods of time. Recent regional efforts to educate producers in year-round finishing methods in order to alleviate slaughterhouse bottlenecks should be encouraged and further evaluated.

Some additional, though less critical, examples of technical advice that would be helpful to producers in the Pioneer Valley include the following:

Recommendations for improving meat producers’ access to such information and services appear in the “Establish a Trade Association for Producers and Processors” section of this report.

Buyer Power in Producer-Processor Relationships

Several pieces of information that producers and processors have shared indicate a lack of individual buyer power in the producer-processor relationship. Processors provide services to producers for a fee; there is no transfer of title of the goods. There are hundreds of producers for each processor. Furthermore, processors must engage in some wholesale trade in order to stay in business year-round. Therefore, each individual producer represents a small percent of each processor’s business. Adams Farm provides processing services to over 100 individual farms, most of which are located in western Massachusetts. However, these western Massachusetts farms collectively represent only 14% of Adams Farm’s total business.15

Overall, meat processors were found to be willing to invest in equipment and new recipes to meet their customers’ demands for new products, but these processors require commitment from their customers of a certain volume and frequency in order to make these investments. For example, a processor may require a producer to commit to paying for 500 pounds of a certain custom-recipe sausage to be processed each month for the next year in order to provide assurance that the costs incurred to update the respective HACCP plan, buy ingredients, and, possibly, purchase a new piece of equipment will be recovered. For smaller producers, it may be difficult to meet these minimum volume commitments. If several smaller producers, however, could aggregate their purchasing power to consolidate the demand for new products and meet that minimum volume requirement as a group, processors could more easily make those requested investments.

While the producers interviewed for this report had mostly positive things to say about the processors with whom they choose to do business, a few first-hand accounts of missing or swapped meat, misinterpreted orders, mismanagement of animals, and scheduling mistakes on behalf of processors did surface. These ‘horror stories’ have a tendency to propagate throughout the agricultural community and become the common perception of what a producer-processor relationship may be like. While this might not be explicitly indicative of an imbalance of power, this sentiment does suggest that producers feel vulnerable in their relationships with processors. Furthermore, these complaints are not particular to one single processor—they reflect attitudes toward this necessary service at large. Meanwhile processors rely upon producers for the business that they bring, but often find it difficult to communicate the vital importance of having a year round, consistent supply of animals coming for slaughter. Recommendations for leveling the playing field and improving the overall relationships between producers and processors also appear in the “Establish a Trade Association for Producers and Processors” section of this report.

Travel and Logistics

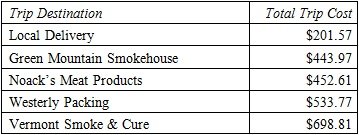

The mean round-trip distance traveled by a producer in the Pioneer Valley to the processing facility is roughly 73.8 miles, with travel time totaling over an hour and fifty minutes.16 This represents an additional expense of roughly $87 per trip17 to producers in terms of vehicle and gasoline usage, which results in an even higher cost of meat products, as well as the large opportunity cost of spending this time away from on-farm activities.

Furthermore, there are currently no affordable logistics services that producers in the Pioneer Valley could hire to deliver their meat products from the processing facility to their farms or to their wholesale customers. Adams Farm does offer delivery services to its customers, but at a relatively prohibitive price point (i.e. $1.75 per mile). While some producers occasionally coordinate their deliveries, loading animals from several farms into one trailer to bring them to the processing facility, and sharing the cost of renting a refrigerated truck to retrieve all their meat from the processor in a single trip, this is not a common practice. None of the processing facilities commonly used by producers in the Pioneer Valley offer affordable delivery services, nor are there any third-party logistics services that specialize in meat delivery.

The producers interviewed in this study are enthusiastic about the idea of using a delivery service to transport their meat from the processing facility back to their farms, as long as an appropriate inventory tracking system were used to ensure that all of their expected meat arrives safely back at the farm. However, they would not likely be willing to outsource the functions of delivering live animals to the processing facility, or delivering their meat products to wholesale customers. The live animal delivery process is often a delicate and an emotional one for producers, and it would be extremely difficult to find a qualified individual whom many producers would entrust with this task. Meanwhile, producers often use their delivery trips to local restaurants and grocery stores as an opportunity to maintain their relationships with these customers, make additional sales, and update them on news from the farm, which, in turn, benefits customers’ marketing efforts. For these reasons, most producers would be expected to continue managing these two activities themselves, even if third-party services were available.

Recommendations for improving local logistics services appear in the “Form a Logistics Service” section of this report.

Variety of Meat Products

All but one of the producers interviewed support CISA’s findings from its 2008 study on demand for meat-processing services,18 in indicating the need for a greater variety of meat-processing options in the local area. The alternative opinion came from a producer who raises only beef cattle, the majority of which are sold wholesale, either whole or in halves or quarters, to restaurants and grocery stores in the Pioneer Valley. Thus, this particular producer has little need for a broader selection of products in his current business model.

Interviewees also noted that since most producers in this area have their meat processed at the same facility, identical recipes are used to make everyone’s products. For example, Adams Farm, the processing facility of choice for five of the seven producers interviewed in this study, uses the same sweet Italian sausage recipe for all of its customers. This makes it very difficult for producers who use this processing facility to differentiate their meat products from one another. They find that their customers, who pay a premium for these local products over what they might spend on conventionally raised meat at the grocery store, want to try new and unique products. Producers who want to meet this consumer demand must then travel from 150 to over 400 miles round-trip on average to regional USDA inspected facilities, which offer a greater variety of recipes. These trips drive the cost of the already expensive products even higher, which further impedes competition in this industry.

In addition to custom recipes for standard products, such as bacon and sausage, the producers who were interviewed also want a greater variety in the types of products that can be made with their meat in this area. Some examples of such products that producers would like to make in order to satisfy customer demand include dry-aged products (e.g. prosciutto and salami), nitrate-free smoked meats, and cased (i.e. linked) sausage.

Finally, locally produced meat in the Pioneer Valley sold through retail is almost always frozen. Fresh meat is only available wholesale to customers wishing to purchase a slaughtered animal whole, by the side, or by the quarter. Producers would like to meet their customers’ demand and sell fresh meat through their retail stands and at farmers’ markets, but the current logistics system, as described above, is not sophisticated enough to support this activity. Producers believe that demand for fresh local meat is too elastic to support the cost of making multiple trips to the processor to retrieve fresh meat before it expires. This too, demonstrates a need for additional logistics services in the area.

Recommendations to address the lack of variety in meat products that can be made locally appear in the “Recommendations to Address Challenges in the Local Meat Industry” section of this report.

Talent Development and Retention

The processors interviewed in this study agree that employee turnover and training is the biggest obstacle to providing their ideal level of customer service. The annual employee turnover rate in the American meat processing industry overall is over 100%, according to a 2005 report by the United States Government Accountability Office.19 While the turnover rate is much lower at smaller, family-owned processing facilities in this region, turnover is still roughly 10-15% annually,20, 21 and remains a significant roadblock to maintaining business continuity.

Furthermore, these processors note that their employees have little to no previous experience in the industry, and that the owners must train all of their employees themselves.

Data on Demand for Local Meat

While all resources used in this study claim that the demand for locally produced food is increasing consistently with no ceiling in sight, and that livestock farming is becoming more popular in the Pioneer Valley, there is still a lack of quantitative data to support these claims.

go to: table of contents | top of section

A variety of different types of businesses and organizations were examined as potential alternatives to improve the options for meat processing in the Pioneer Valley. Examples of such options are discussed below within the major categories of Meat Processors, Trade Associations, or Multi-Producer Marketing and Branding.

Meat Processors

Slaughterhouses

Slaughterhouses historically focused their business upon the slaughter and cutting of animals into primals, which would then be further processed by distributors, butchers, or supermarkets for retail sale. As discussed previously, with the growth of the local food movement, demand from meat producers has expanded significantly for attractive packaging, retail-cutting services, and the creation of other value-added products, especially types of charcuterie. Today’s slaughterhouses, however, still largely offer only limited post-slaughter processing options, leaving producers in search of secondary processors or stuck with a lack of product diversity.

Butcher Shops

Classic Butcher Shop

In the past, local butcher shops fulfilled any meat-processing needs for consumers beyond what was provided at slaughterhouses. Today, with the widespread occurrence of supermarkets, and other market pressures for consolidation in the food industry, the traditional model of a classic butcher shop has diminished greatly. Instead of receiving primals and breaking them down into a wide assortment of retail cuts, today’s butcher shops, mostly existing in supermarkets, generally receive ‘boxed beef,’ or the smaller subprimal cuts, such as tenderloins, which have already been cut from the larger primal cuts, like the loin, prior to delivery. The demand for skilled butchers, and thus the availability of these skills, has greatly diminished in light of these changes. Some butcher shops, such as Pekarski’s in South Deerfield, Massachusetts, however, still prepare a variety of meat cuts and products, though these shops generally sell their products under the USDA FSIS Retail Exemption, without USDA inspection. Under the Retail Exemption, these butchers are not able to provide their services to producers who would like to have their meat processed for their own retail sale, since the Retail Exemption prohibits the manufacture of products for other retailers.

Mixed-Service Butcher Shop

Another example of a retail butcher shop is The Meat Market in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. As the classic model for a butcher shop typically provides low margins to owners, The Meat Market has built a successful business by also incorporating a restaurant, catering services, and artisan charcuterie. Only through combining these multiple streams of revenue is the business truly viable. Again, as with Pekarski’s, The Meat Market currently operates under the Retail Exemption, and could not process meat for producers wishing to retail themselves.

Commercial Butcher Shop

An example of a larger butcher shop that does offer USDA inspected meat processing for producers is Westerly Packing in Westerly, Rhode Island. Similar to The Meat Market, Westerly Packing has a multi-stream revenue model. In addition to its retail butcher shop, the company also operates a large distribution service for restaurants, delivering meat and other food products, condiments, and spices, as well as paper goods and cleaning products. Again, it is through the use of multiple revenue streams that the business has been able to grow and be quite successful. Fee-for-service commercial meat processing for local producers makes up a small portion of its total business, but is desirable because the business must already be USDA inspected in order to operate its distribution service. Westerly Packing is the exclusive butcher for the Rhode Island Livestock Association, which is discussed below.

Vermont Smoke and Cure in Hinesburg, Vermont is another model for a hybrid USDA inspected meat processor and butcher shop. The company produces its own line of sausages, bacons, hams, and other smoked meats, which are distributed throughout New England to a variety of natural-foods stores and supermarkets. While it is a small part of their business, Vermont Smoke and Cure also offers fee-for-service meat processing to individual meat producers, largely resulting from the company’s desire to support the local meat industry. Although some meat producers in Massachusetts have used Vermont Smoke and Cure’s processing services, the facility is located almost 200 miles away from the Pioneer Valley, making it cost-prohibitive for the majority of individual local producers to access.

Supermarkets

The decline in stand-alone butcher shops coincided with the rise of supermarkets. Most supermarkets operate some type of retail butcher shop within their store. As discussed before, these butcher shops largely receive pre-cut meat, and, therefore, have little need to employ skilled butchers, greatly restricting the availability of these skillsets in the local meat industries that need them. Because supermarkets sell directly to household consumers, they typically operate under the USDA FSIS Retail Exemption, and, therefore, are unable to provide processing services to commercial producers.

Restaurants

Often, higher-end restaurants will purchase whole animals or primals in order to create their own meat cuts and products. As with classic butcher shops and supermarkets, most restaurants are not USDA inspected, and, therefore, could not process meat for producers to then resell. At a certain scale, some restaurants may consider setting up their own USDA inspected processing facilities in order to distribute the meat products that they currently create for diners through other wholesale channels to household consumers, as well as hotels and restaurants. The Farmhouse Group in Burlington, Vermont is an example of such a model, as they currently operate three restaurants, and will soon open a USDA inspected meat processing facility, as well as an associated butcher shop and delicatessen. In this model, meat processing is primarily undertaken as an extension of the restaurant’s own business and brand. As with Vermont Smoke and Cure, it is possible that a restaurant might make its processing services available to individual high-volume producers at premium prices, in order to use up any excess capacity available in their USDA inspected facilities.

Commercial Kitchens and Food Hubs

Opening recently in January 2012, the Mad River Food Hub in Waitsfield, Vermont is an example of a commercial kitchen that has been established to serve both entrepreneurs making vegetable based products as well as producers who wish to create value-added meat products. Mad River is USDA inspected, and offers their patrons two meat processing rooms, as well as a large amount of refrigerated and freezer space. The processing rooms include the equipment necessary to cut, grind, and smoke meat, as well as create other value-added products, such as linked sausages. Mad River is also in the process of adding new equipment so that individuals can create dry-cured meat products, like salumi. Individuals can rent processing space by the day and storage space by the month in order to process meat or other products themselves. Mad River’s staff is trained in butchery, and can assist those new to commercial meat processing with getting started. In the past, Mad River has offered a fee-for-service co-packing option, making food products for producers, instead of renting them space in which to process their own products. Since the mission of Mad River is intended to provide kitchen, storage, and distribution services to enable entrepreneurs to launch new businesses, and not to manufacture products for them, the company is planning to spin off co-packing to a non-staff individual who will provide these services as a separate business.

A commercial kitchen in Greenfield, Massachusetts has also been in operation for several years. The western Massachusetts Food Processing Center, part of Franklin County Community Development Corporation, is currently focused on processing non-meat products, and is not USDA inspected. This facility, however, has significant promise in helping to provide low-volume producers with expanded options for value-added products, as described in this report’s “Establish Fee-for-Service Meat Processing at a Local Commercial Kitchen” section.

Trade Associations

The Rhode Island Raised Livestock Association (RIRLA) currently has a membership base of over 120 regional producers, from Rhode Island and neighboring states, plus other stakeholders in the local food system.22 RIRLA was founded in 2006 by a group of local producers to accomplish the following:

Through aggregating their demand for local meat processing services, Rhode Island livestock producers gained access to USDA inspected livestock slaughtering services at Rhode Island Beef & Veal in Johnston, Rhode Island and cutting and processing services at Westerly Meat Packing Company in Westerly, Rhode Island.

Prior to the establishment of RIRLA, Rhode Island’s small producers could not, as individuals, provide enough consistent demand to do business with Rhode Island Beef & Veal, which primarily services and buys livestock from larger regional meat producers. Today, RIRLA provides small Rhode Island producers access to slaughter at Rhode Island Beef & Veal. Collectively, they represent an estimated 1-5% of Rhode Island Beef & Veal’s overall business. Once the livestock is slaughtered, Rhode Island Beef & Veal drives the carcasses approximately 50 miles from Johnston to Westerly for processing. After the meat is cut and packaged at Westerly Meat Packing Company, producers must then drive to Westerly to pick it up.

Another regional association, the Northeast Livestock Processing Service Company (NELPSC), is based in the Hudson-Mohawk region of New York. Their mission is to make custom processing stress-free for producer members, while also increasing the profitability of northeast family livestock farms by assisting with marketing. NELSPC has 139 members from 24 counties, and works with eleven different livestock processors.23 Specifically, NELPSC provides consulting services, especially to those new to livestock farming, in areas such as slaughter scheduling, guidance on cuts and processing logistics, and issue resolution. The organization also helps its members fill slaughterhouse slots, or share product as needed between producers. Meanwhile, NELPSC has sought to create new markets for its members’ products. This has primarily taken the form of serving as an approved vendor to a distributor of meat products for institutional accounts, primarily regional universities. Since the requirements to become an approved vendor are beyond the capacity of most individual producers, NELPSC has created an entirely new market for its members’ livestock, which they could not access previously. The company pays a premium price to their members for the livestock, and coordinates all transportation to and from local processing facilities to the purchasing institutions. Similar strategies involving aggregation, distribution, and institutional markets may be applicable to western Massachusetts, although the number and size of farms, the price of land and some costs of production may differ in ways that impact price points that allow for farm economic viability.

Multi-Producer Marketing and Branding

Another model that has been successful in strengthening local meat industries is that of a multi-producer brand. Local producers operate as a single unified brand, all raising their livestock under mutually agreed upon conditions. Cooperatively owned multi-producer brands include Painted Hills Natural Beef in Oregon, Country Natural Beef throughout the West Coast, and Good Natured Family Farms in Missouri. In Massachusetts, Northeast Family Farms purchases livestock raised throughout New England to sell under its brand. Meanwhile, Hardwick Beef has created a strong brand of grass-fed beef throughout New England by working with regional producers. Black River Produce similarly sources locally raised meats for its distribution service, and has recently opened a USDA inspected meat-processing facility to increase their capacity and control over when and how the meat they sell is processed. Larger brands, like Black River Produce, are both better able to satisfy demand for a consistent supply of locally sourced meat, and to generate sufficient volume to profitably manufacture value-added products. For local meat producers, selling livestock to these multi-producer brands provides much lower margins, but allows a producer to devote less time to processing, marketing, and sales, and therefore save on numerous opportunity costs.

go to: table of contents | top of section

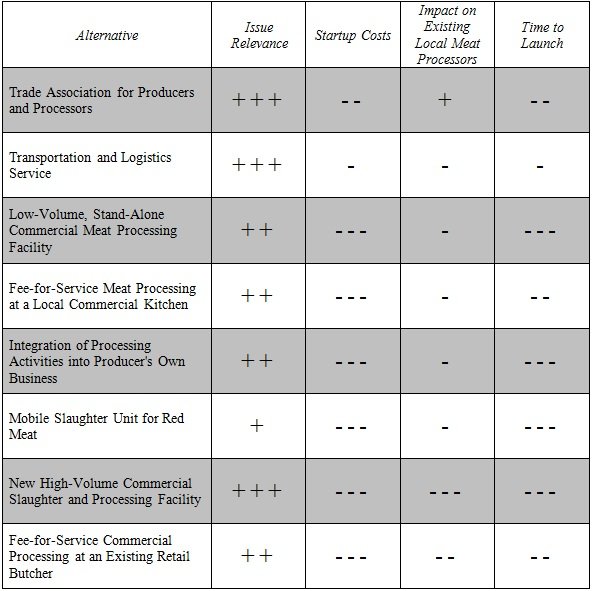

Criteria Used

In the consideration of all options to improve the local meat infrastructure, the following criteria were used in a multi-goal analysis of all alternatives:

Issue Relevance

To what extent the alternative addresses the challenges for producers described in the report’s findings from primary research, such as the lack of options for processed meat products, imbalance of power in producer-processor relationships, high transportation costs, and so on.

In the alternatives decision matrix shown in Exhibit 2 below, alternatives are marked with a “+” sign for each of the following areas the option is likely to improve:

Startup Costs

How much would it cost to launch this new venture? Initial capital expenditures are included as the primary driver of this criteria, with additional consideration for the operational effort required to sustain the organization and an assessment of the risk carried by the alternative in terms of its effect on entrepreneurship.

In the alternatives matrix, alternatives are marked with one “-” sign for minimal capital outlays, operational effort, and risk; two signs if moderate; and three signs if the projected costs are major.

Time to Launch

How long would it take for this alternative to become operational, and begin to address the challenges faced by local producers?

In the alternatives matrix, alternatives are marked with one “-” sign if the expected time to launch is less than six months, two signs if less than one year, or three signs if greater than one year.

Impact on Existing Local Meat Processors

To what extent would the alternative affect existing commercial meat-processing facilities? For instance, an alternative that would compete for the customers of an existing local meat processor would be rated negatively, whereas an option that would support the business interests of a local processor by strengthening commitments from producers would be rated positively.

In the alternatives matrix, alternatives are marked with either “+” or “-” signs, depending on whether the option is expected to help or harm existing meat processors. One sign is used if the impact is assumed minimal, two signs if moderate, and three signs if major. As seen on the next page in Exhibit 2, all alternatives confronted during the research for this report were judged by these criteria.

Exhibit 2: Alternatives Decision Matrix

The latter four alternatives presented in Exhibit 2 above scored relatively low on these criteria with respect to the first four items on this list. For this reason, they have not been explored further in this study. A more detailed explanation of why these four alternatives are not currently the most beneficial options in the Pioneer Valley will follow in the next section of this report, titled “Alternatives Not Explored Further.”

Alternatives Not Explored Further

Integration of Processing Activities into Producer’s Own Business

Although a producer could conceivably integrate a USDA inspected processing operation into their existing business of raising livestock and marketing meat products, this option is not particularly common for a variety of reasons.

First, the establishment of a processing facility requires significant capital investment, primarily for the building and equipment. Such expenditures would generally require a producer to recoup those costs either through expanding their own business to leverage the full capacity of such a facility, or offering fee-for-service custom or commercial processing to other producers and homesteaders. As local producers are typically of a scale far below what would be required to operate an exclusive facility, the prior option does not seem feasible in this context. Additionally, while some processors do manage their own herds, they are often used to provide income in periods of low demand for their processing services, and do not make up a major revenue stream for those operations. Ultimately, the businesses of raising and processing animals are very different, with few opportunities for synergy by combining these types of businesses on just a small scale.

Further, state and USDA regulations require both custom and commercial slaughter and processing to be conducted in an approved facility. Massachusetts does not have a state meat inspection program, so any producer wishing to sell meat products to consumers must have their animals processed in an USDA inspected facility. Alternatively, a producer may sell live animals to one or more household consumers, and then facilitate the custom processing of those for the consumers under a USDA FSIS Custom Exemption. In Massachusetts, this processing must occur in either a custom or commercial slaughterhouse, and not on a producer’s farm, which would not meet the state’s requirements to prevent the adulteration of food. Massachusetts requires that custom processors receive periodic sanitation and recordkeeping inspections from the Department of Public Health.24 Producers in some neighboring states, such as Vermont and New Hampshire, however, may, through varying state regulations, slaughter and process live animals sold to customers on their farms. Some states always require the farm to use a custom processing facility, while others allow a small number of animals to be processed outdoors, outside of a facility. All custom and commercial slaughtering in Massachusetts must be done in an approved facility licensed by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Mobile Slaughter Unit for Red Meat

Mobile processing units have received increased attention in recent years as an ultra-local solution to the slaughter and processing challenges of small-scale producers.25, 26 The USDA FSIS is interested in finding solutions that work for smaller producers, and leveraged the flexibility provided through HACCP regulations to make inspection possible for new types of slaughter and processing facilities. Still, the establishment of a mobile processing unit for red meat in western Massachusetts was precluded as an alternative for several reasons.

Primarily, mobile processing units facilitate on-farm slaughter, and not usually on-farm processing. Most models require the use of a physical facility where the carcasses are transported to for aging, cutting, processing, and packaging. For many of the challenges faced by local producers, such as access to additional processing options and improved quality and consistency, this model does not seem to provide any improvements. If anything, the use of a mobile unit for slaughtering could detract from the business of local processors who already provide these services. Also, many desired value-added products must be cured, and often smoked, which generally require the use of specialized equipment and facilities for extended periods of time.

Secondly, anecdotes of severe under-usage are prevalent surrounding a recent venture to create a mobile poultry-processing unit in Massachusetts. Therefore, the local meat community may currently be more skeptical of supporting this type of processing solution, especially with the high switching costs incurred by producers when moving from one processor to another.

Lastly, mobile processing units tend to be financed through a combination of private donations, cooperative investment, and rural development grants. The need for many of these facilities is often underscored by a true lack of local slaughter and processing options, brought on by the closure of a valued local facility, and not the need for a solution that provides more processing options and convenience, as required in western Massachusetts. Although the concerns of local producers around processing may seriously affect their business, in general they relate to a desire of the producer to diversify their product lines or expand their business, not simply stay in business, and thus may not demand the same type of community investment as seen in other situations.

New High-Volume Commercial Slaughter and Processing Facility

While rumors of dissatisfaction abound, no significant complaints about local slaughter facilities were voiced by the Pioneer Valley livestock producers interviewed in this study. In fact, one local processor, Adams Farm, has a new, state-of-the-art, and high-welfare slaughter facility, which is valued highly by local meat producers. Further, this particular operation is not currently operating at full capacity, and would prefer to do more work for local livestock producers, instead of expanding its religious and regional slaughter segments. Although our interviews also suggest that there is some room for improvement in customer service and consistency in quality at existing processors, the establishment of a new slaughterhouse is not the simplest route to this goal, nor does it guarantee this result.

Similarly, existing processors have expressed a desire to increase their post-slaughter processing options, including the production of new types of meat products. These processors, however, often require some assurance of future processing volume in order to warrant investment of capital into new types of equipment, and of time into the development of new product recipes and labels. Therefore, aggregating demand from local producers for new processing services in order to reach the necessary volume thresholds is preferable to launching a new facility, which would likely require the same commitments. Such aggregation of demand and group-level communication with local processors could be facilitated through the activities of a new association for local meat producers as described in the “Establish a Trade Association for Producers and Processors” section of this report. In this report, post-slaughter processing for individual producers in amounts below the thresholds required by local processors are designated as ‘low-volume’ processing, and in amounts above the thresholds as ‘high-volume’ processing.

Fee-for-Service Commercial Processing at an Existing Retail Butcher

Originally, the alternative of adding processing services at a local butcher shop was considered as an option. This alternative was attractive for many reasons. First, it could add an additional revenue stream to an existing retail butcher shop. Also, this option would not require the establishment of a new meat-processing facility, and would leverage the expertise of a veteran meat cutter.

However, as discussed previously, in order to process meat products for producers to then sell, the butcher shop would need to become USDA inspected. Unless the volume of business available was significant, or the butcher shop had an additional reason to become USDA inspected (such as a desire to sell its branded products through wholesale distribution channels), this alternative is unlikely.

go to: table of contents | top of section

Introduction

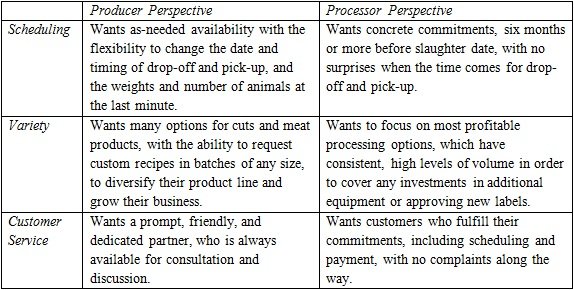

Achieving success as a small-scale meat producer requires a strong relationship with a local meat processor. The local meat industry is without many parallels, as the goods (i.e. livestock) must be delivered to a service provider (i.e. processor), then retrieved as processed goods (i.e. meat cuts and products), and next moved down the value chain to consumers. USDA regulations, plus significant capital investments needed for facilities and equipment, make it practically impossible for small producers to incorporate processing into their own businesses. Furthermore, the obvious comparison consumers make between the prices of local and commodity meats make it difficult for producers and processors to grow their margins, even in a market for niche products. Therefore, it is essential for producers and processors to work together to ensure that both parties help each other meet their business goals to the best of their respective abilities.

From a producer’s perspective, an ideal processor would always be available to accept animals that are ready for slaughter. Maybe the processor would come to the farm to pick them up, or even slaughter them on-farm and bring the carcasses back to a central location for aging and processing. The processing options would be many, consistent, and of the highest quality. Service fees would be as minimal as possible, and above all, fair. Finally, the product, fresh or frozen by the producer’s choice, might be returned to the farm in a refrigerated truck, separated into individual boxes and sorted in accordance with a producer’s inventory system. There would be no doubt that the products delivered were made from the producer’s livestock or that any products might be missing. The goods would likely be accompanied by a detailed list of cuts, weights, and products delivered, maybe even with a barcode-type system for easy acceptance and transition into the producer’s refrigerators or freezers.

From a processor’s perspective, an ideal producer would plan their production a year in advance. There would be no surprises, and the projected amount of animals would be delivered on time, every time. Producers in the processor’s region would work together to spread out their production over the year to provide smooth and regular demand for services. Certainly, level business demand would help the processor best manage its employee base in order to retain highly skilled and dedicated workers. Producers would always pick up the product as soon as it were ready, thereby reducing storage costs, and would never need to question the processor’s tracking system, quality, or quantity returned. Producers would be happy to pay a margin that reflects the processor’s fair profit goals, which helps it grow and maintain its operations. These contrasting ideal scenarios are summarized below in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3: Ideal Producer-Processor Relationship from Each Party’s Perspective

For most local meat producers, few options exist for slaughter and processing facilities. Generally, producers must travel 50 to 100 miles or more to deliver their livestock to processors, only to make the journey again in a few weeks to pick up their meat. Furthermore, producers often transport their livestock and meat products independently, and do little to minimize their costs as a regional group of producers. Some producers wish that they could pay less for processing, have more options for products that can be made with their meat, or at least see the availability and consistency of existing services improve. Other producers express frustration about the customer service they receive from processors, and vice versa. While producers may complain about how long it takes to schedule processing for their livestock, processors also criticize some producers for making last-minute changes in timing or quantity. Sometimes processors need to take on some larger, more commodity-type business, such as processing of halal or kosher products, just to keep the doors open. These situations represent inefficiencies in the fragmented value chain for local meat products that make it difficult for all members to manage their businesses.

Additionally, new livestock producers enter the local meat industry each year, with a need to learn how to best work with their regional processors. Each processor, for example, has different protocols for how producers should deliver and retrieve their products. New producers are especially burdened with learning all the complexities of their local meat processing system, namely options for meat cuts on an animal, conversions from live to finished weight, and scheduling timeframes. Producers come from a variety of backgrounds, not necessarily animal husbandry or business, and often have questions about how to most profitably break down their livestock into certain cuts and products.

Despite the fact that they do not have much time to spare and operate on small margins, small- to medium-scale processors routinely consult with producers on their production plans, and help new producers understand all their options. For example, it is not uncommon for a new producer, or even a veteran, to ask a processor to make certain cuts from the same animal that are actually mutually exclusive. The processor knows that he can make one cut or the other—not both—but the producer might not, which inevitably leads to inefficient back and forth that strains already small margins. Similarly, many producers desire new value-added products, such as specialty sausages and charcuterie, from their processors and have trouble understanding why processors often are reluctant to produce new items, often citing regulatory, legal, and capital concerns.

Perhaps it will always be the processor’s responsibility to educate their customers. Or, could this task be something that a local network of producers adopts? After all, some producers understand the local processing systems quite well and could share this information with others. Competition in the local meat industry tends to be defined by camaraderie rather than rivalry; while producers are generally independent and heterogeneous in practices and products, they also understand that many livestock farms must exist to keep local small-scale processors in business. Of course, the other option is to follow the lead of the commodity meat industry and grow a farm to an industrial scale that could support its own processing facility, but this alternative seems to be the antithesis of the local food movement.

Value Proposition

For the reasons previously discussed, the establishment of an organization to support the interests of local meat producers and processors is recommended. This organization, referred to as the western Massachusetts Meat Association, or WMMA in this report, aims to provide small meat producers in western Massachusetts with a range of activities that support their businesses, while implicitly providing benefits that serve local processors as well. The vision and mission statement of WMMA could be similar to the following examples:

Vision Statement

To coalesce the shared business interests of livestock producers and processors in western Massachusetts, and to advance an efficient and thriving market for local meats.

Mission Statement

The western Massachusetts Meat Association (WMMA) provides a unified voice for local livestock producers; builds relationships among producers, processors, and consumers; advances members’ common business interests, and promotes member empowerment through knowledge-sharing and other collaborative efforts.

Operational Model

WMMA would serve the interests of livestock producers in western Massachusetts through a variety of business support activities, including, but not limited to, the following:

Primary Services

Ancillary Services

Financial Model

WMMA would operate much like a trade association and need to generate the majority of its operating budget through member contributions. Trade associations are typically funded through business memberships, donations, and value-added fee-for-service activities, such as product certifications and business consulting.

Unlike a trade association, WMMA would seek to promote member independence, in order to preserve the diversity of production and business practices that is necessary to protect the heterogeneous nature of local food systems.

Initial Funding

A combination of grants, business donations, and in-kind contributions, such as hours volunteered, will be necessary to provide the start-up capital for WMMA. Although WMMA would endeavor to become a self-sustaining organization in three to five years, external capital will be required to hire a Director who will then begin to generate revenue through securing members, providing consulting services, and facilitating access to local processors.

Expenses

Part-Time Director: The salary of a part-time Director will represent the majority of WMMA’s operating budget. We project an annual salary of approximately $25,000, commensurate with experience, for 1,000 hours of annual work, or an average of 20 hours per week. If an individual with significant experience, however, is hired into the Director role, instead of a person that would require significant on-the-job training, the $25,000 half-time salary may too low. Still, about half of the hours worked by the Director would be revenue-generating, spent on a mix of membership, consulting, and scheduling services, and the remainder would allow for pro-bono consulting, communications, marketing, and other activities, as defined above. Therefore, a person with more experience in consulting would be a preferable candidate for this position.

Other Expenses: A projected amount of $5,000 to $10,000 will be spent on general and administrative expenses related to office supplies, accounting, insurance, telephone and computer, website, postage, printing, mileage, etc. The Director will likely work remotely with a cellular phone and computer provided by WMMA, plus reimbursement for traveling to producers or processors.

WMMA should also plan to conduct a number of educational workshops and membership meetings, intended to facilitate the exchange of ideas and the development of business and technical skills, with each workshop costing $800 to $1,000 to design and deliver. Attendance fees will often cover a large portion of the cost of each workshop, but WMMA still expects to incur total expenses of roughly $2,000 per year for workshops that will not be recovered by admissions.

Main Revenue Streams

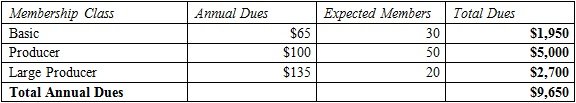

Membership Dues: WMMA is expected to generate about 25% of revenues from membership dues. In contrast, membership dues for the Rhode Island Raised Livestock Association accounted for approximately 20% of the organization’s operating budget in 2012.

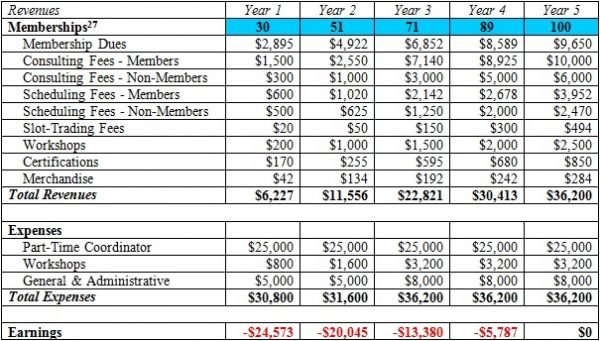

WMMA’s membership base is anticipated to grow to 100 after five years, paying average dues of almost $100 each, as shown below in Exhibit 4. CISA currently lists 59 meat and poultry producers in its online database. We expect that these producers will join WMMA, in addition to new and existing producers who are not currently CISA members. Comparatively, Massachusetts Farm Bureau Federation, which represents both livestock and produce producers, boasts a membership base of over 6,400 families in Massachusetts, charging annual dues of $180 for “Regular Farmer Members,” $300 for “Gold Club Members,” and $60 for non-farmers.

Exhibit 4: WMMA Memberships After Five Years of Operation

Basic WMMA members are either non-producers or homesteaders who process up to four animals per year. Restaurants, retailers, and other institutions that do business with WMMA producers will also be encouraged to support the organization by purchasing a basic membership. Producers are the typical WMMA member, processing five to ten animals per year. Large producers will likely process more than ten animals per year.

Producer or Large Producer membership with WMMA will include one free consulting hour per year, which will generally take the form of a planning-type meeting during which the WMMA Director assists the producer in planning livestock production for the coming year, or in starting to develop a twelve-month marketing strategy.

Membership with WMMA provides access to educational resources, such as workshops, newsletters, and member forums; access to regional production data and benchmarks; assistance in aggregating product with other members to engage higher-volume channels; as well as relationship management and conflict resolution with processors and other producers, as needed.

All WMMA members will also be able to take advantage of heavily discounted consulting services at only $50 per hour, as well as access to ‘as-needed’ or ‘last-minute’ scheduling slots (discussed below) at local processors for a $10 fee. WMMA members will also be able to trade their ‘as-needed’ slots with other members for a $10 facilitation fee.

Consulting Fees: Business, technical, and regulatory assistance is expected to make up WMMA’s largest revenue stream, or roughly 45% of the organization’s operating budget. Primary research has revealed an absence and lack of awareness of the value of consulting services for livestock producers. Some regional organizations, such as Farm Credit East, already provide business-consulting activities to different types of producers, indicating local demand for these services. These engagements are often project-based, and although they can be quite valuable, total project costs can also be expensive. WMMA will offer flexible and highly available consulting services to local producers as needed. WMMA’s expertise will also be focused on the western Massachusetts meat market, with an acute awareness of local demand and strategic opportunities. Each member is anticipated to contract an average two hours of consulting per year at a total cost of just $100.

Although many meat producers are able to operate profitably without these types services, many have also expressed a desire to learn more about how to better market, price, and advertise their products. Furthermore, some producers often struggle with understanding the most profitable way to process their animals into different cuts and value-added products. WMMA anticipates considerable demand for low-cost business support services from producers in western Massachusetts. Many of WMMA’s consulting services also have the opportunity to benefit non-livestock producers, who are also expected to engage the organization for business analyses and recommendations. Additionally, consulting may take the form of the Director accompanying a producer’s livestock along their route in the slaughter and processing facility, helping to assure humane handling, quality cutting and further processing, and accurate tracking and labeling.

WMMA will also assist producers and new processors in navigating the regulatory landscape of the meat industry, related to procuring labels for new meat products; creating HACCP, SSOP, and other food-safety plans; understanding facility, inspection, and equipment requirements; and more. Unlike individual businesses, which infrequently deal with challenging regulatory guidelines, WMMA’s Director will consult on these matters routinely, enabling the efficient and practical delivery of regulatory advice, preserving members’ time, money, and peace of mind.

Scheduling Fees: The last major revenue stream for WMMA will be income earned from providing highly available processing slots to local producers and homesteaders. Unlike RIRLA, which has exclusive rights to slaughter and processing services at local facilities, and can therefore demand a compensating fee from members to access these services, producers in western Massachusetts can access processors without any sort of provision from WMMA. Therefore, where RIRLA generates almost 80% of its operating funds from scheduling fees, WMMA expects to earn less than 20% of its revenues from these sources.

This financial model assumes WMMA will be able to reserve 10 processing ‘slots’ each week from local facilities, consisting of roughly 3 beef, 4 hog, 2 lambs, and 1 goat. Typically, these slots will not be used for routine processing needs, as WMMA intends to assist producers in planning for their yearly processing needs well in advance of the ultimate slaughter and processing dates. Instead, WMMA expects most of these slots to be used by new producers and homesteaders who are not yet experienced in planning their yearly production. Producers in emergency situations will often use these slots, such as in the case of injured animals or when livestock is not quite ready for slaughter at the planned processing date. WMMA will charge $10 per slot for members and $25 for non-members.

Members will also be able to ‘trade’ reserved slots with one another for a $10 fee. Trades will generally occur when all of the available slots for a week have been reserved and a member has an emergency need to access a slot. In these cases, members will be able to ask the Director to contact all producers who have reserved a slot that week to see if any person is willing to exchange his or her slot for a future slot. Similarly, if a member reserves a slot, but then is unable to deliver an animal on the scheduled date, WMMA will trade that reserved slot for a future slot.

Other Revenue Streams

Outside of income generated from membership dues, consulting, and scheduling fees, which represent 90% of the operating budget in this projection, WMMA will draw revenues from other sources, such as workshops, certifications, and merchandise.

Workshops: As supplying members with educational resources for the local meat industry is one of organization’s key activities, WMMA will hold workshops on meat cutting, value-added products such as dry-cured charcuterie, carcass yields, business optimization, marketing channels, and other helpful technical and business topics. Members will often provide the Director with input on what subjects to cover in upcoming events, and offer recommendations on which speakers and formats would be most appropriate. Some WMMA members with expertise in particular areas may be invited to facilitate a workshop and be compensated for the effort. WMMA will charge members an average fee of $25 to attend a workshop, which may include food, beverages, and supplies. RIRLA currently schedules at least four workshops per year on a variety of topics and attracts between 10 and 30 attendees for each.

Merchandise: As is common in many organizations, WMMA will sell branded merchandise, such as tee shirts, hats, and tote bags. Although these sales are not expected to bring in more than a few hundred dollars per year, they will serve to increase awareness of the organization’s brand and to promote its visibility.

Certifications: Many trade associations offer certifications to their members and external communities in order to enhance the credentials of a product, business, or individual. Although WMMA will advocate for the interests of all members regardless of certification, some producers and processors may ask the organization to evaluate certain aspects of their businesses according to best practices established and maintained by the WMMA staff and Board of Directors. For example, a producer who endeavors to increase demand for grass-fed beef by creating weekly recipes for their customers may qualify for special recognition. This producer may realize premium placement at WMMA-sponsored events, receive special acknowledgement from the WMMA community as a type of business that exemplifies the vision of the organization, and ultimately earn a premium for their products in accordance with the additional value placed on them by consumers. The true value of any certification though, is largely expressed in terms of how it is recognized by the public, which depends on the visibility of the organization and the regard in which it is held. Therefore, we expect certifications to become a part of WMMA’s strategic plan at least five years after launch, when the organization has solidified its standing in western Massachusetts’ local food system.

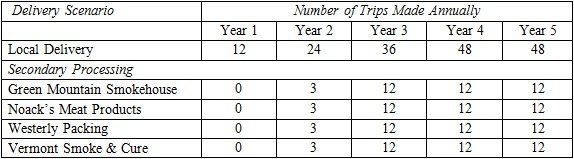

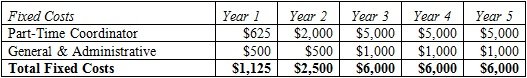

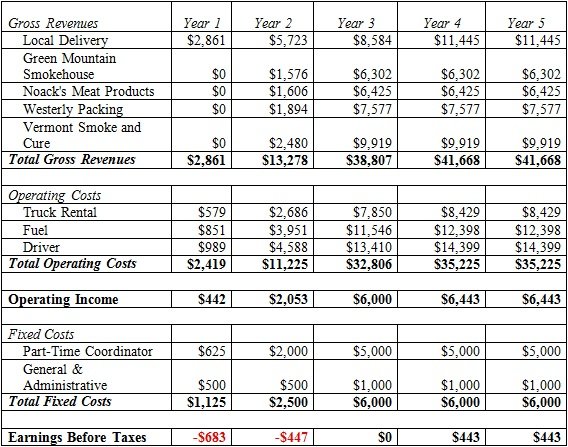

Exhibit 5 on the next page is a projection of WMMA’s revenues, expenses, and earnings for the first five years of its operation, at which point it will become self-sufficient. WMMA should expect to raise roughly $60,000 in grants and other supplemental funding in order to remain in operation for the first four years until it becomes self-sufficient in Year 5. Such grants may be available from the USDA, the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR), and non-governmental organizations that support local agriculture.

Exhibit 5: WMMA Projected Earnings

Ownership Structure

There are a few possibilities for governing WMMA, including ownership by an existing non-profit organization (e.g. CISA) or by an independent group of producers. Ultimately, credibility is paramount in any type of trade association, which requires participation in the decision-making processes by a number of individuals and businesses respected in the industry.

Board of Directors

WMMA’s credibility will likely come from a board of local producers, processors, and food advocates, either in the form of an official Board of Directors for the corporation, or as an advisory board responsible for providing recommendations on the organization’s strategy and objectives. This sort of collective partnership from an assortment of perspectives is absolutely essential for WMMA. In spirit, WMMA endeavors to unite the business interests of independent participants in the value chain for local meat products in such a way that maximizes efficiencies while promoting diversity.

Early on in WMMA’s development, the formation of a board with a balanced approach to growing the local meat will largely determine it success and endurance. Further, depending on the interest of local talent in filling the Director position for WMMA, the board may have to invest significant time in training the new Director to help them fulfill all of their responsibilities. Such a period of relationship building and knowledge sharing between the new Director and the local meat community might consist of sharing information about local production and processing challenges, opportunities for industry collaboration and growth, and continuous networking in order to build community trust with the fledgling association.

The following makeup for an initial advisory board or Board of Directors, all located in western Massachusetts, is recommended:

For a fair representation of the attitudes of western Massachusetts producers at large on the Board of Directors, the three commercial livestock producer members should be diverse in terms of the species of livestock raised, amount of experience in the industry, counties in which their farms are located, and marketing and sales channels used.

Ownership Options

CISA-owned and operated: Operation of WMMA could be included as an activity of CISA’s organization, which could potentially enhance the value of a producer’s CISA membership. As CISA is already active in supporting local producers, and lists over 50 producers selling meat and poultry on its online database, we see the objectives of WMMA as a natural extension of the services CISA already provides to its member producers. Further, since a primary goal of WMMA is to help educate producers on local slaughter and processing options, as well as best practices in meat production, ownership of WMMA would underscore CISA’s commitment to a robust local food system. We expect producers to perceive WMMA as a high-value initiative, which could reflect favorably on CISA’s brand.

CISA may consider adding a new membership level to the Local Hero program (ex. Platinum Level), possibly at a higher price point than current membership levels, which includes provision of the processing scheduling service and access to WMMA’s other resources for producer coordination and education. Alternatively, CISA may choose to provide these services to current member producers free of additional charge, if such an arrangement is affordable to the organization and able to be combined into existing activities.

The largest single expense for WMMA is the part-time salary (~$25,000/yr.) for the single employee acting as the Director of the association. This salary would likely represent between 50-65% of WMMA’s operating expenses. If CISA were able to allocate the equivalent of 20 hours per week of labor from current employees to WMMA, then this would greatly reduce WMMA’s operating costs. Furthermore, an additional 10-15% of WMMA’s operating expenses include general administrative expenses, such as telephone, accounting, website maintenance, and other services, which might be shared with CISA.