In a Class by Itself

UMass Dining Makes Degrees of Progress

“Come for the food; stay for the education.”

“Come for the food; stay for the education.”

That was perhaps the most memorable, and repeated, remark offered by UMass Amherst Chancellor Kumble Subbaswamy at ribbon-cutting ceremonies last fall for the renovated Hampshire Dining Commons in the campus’s Southwest residential area.

And the comment speaks loudly to what would have to be called the meteoric rise of UMass Dining, an $80 million, self-sustaining operation that is one of the largest of its kind in the country, if not the world, and now also one of the most heralded.

It’s unlikely that any of the 28,000-odd students attending the university this past year came just for the food, but it’s fair to say it was a factor for many of them, which is something that could not have been said until … well, after Ken Toong arrived on the scene nearly 16 years ago.

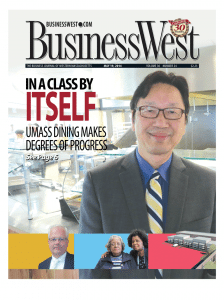

Now a certified rock star in the dining-services universe, Toong, executive director of Auxiliary Enterprises for the university, which oversees a number of operations, including UMass Dining, changed the way the school thought about food and food service. He is credited with orchestrating a stunning turnaround for an operation that for decades was an afterthought — if it was thought about at all.

This resurgence is about much more than better-tasting food and more choices, although those are big parts of the recipe for success. It’s also about promoting healthy eating habits, buying local, sustainability — and fun, such as setting Guinness Book of World Records marks for the largest stir fry (4,010 pounds), seafood stew (6,656 pounds), and fruit salad (15,291 pounds) over the past three years.

There are myriad ways to measure the success achieved by Toong and his staff.

For starters, there’s a host of numbers and statistics concerning trends and programs within the operation. These include:

• A 15% increase in student consumption of fruits and vegetables over the past year;

• A 30% reduction in sodium in recipes;

• An 18% decline in the consumption of sugary drinks;

• Steadily climbing consumption of seafood; UMass students now eat 21 pounds of it a year, on average. Nationwide, the number is 14 pounds;

• A rise in the number of students on the meal plan from roughly 8,400 when Toong arrived to more than 17,000 in 2013;

• A sharp increase in the amount of produce the university buys locally — from roughly 8% a decade ago to nearly 40% today; and

• A so-called ‘missed-meal’ mark of 10%; 15 years ago, it was nearly 40%.

There are also awards — the dining service was rated the third-best in the nation by the Princeton Review in 2013, and first in University Primetime’s ranking of the 50 Best Colleges for Food in the U.S., for example — as well as comments such as the one offered by Subbaswamy and a number of visitors from other colleges who come to UMass Amherst to learn about the dining operation; Harvard, Yale, Buffalo, and UCLA have all been in recently.

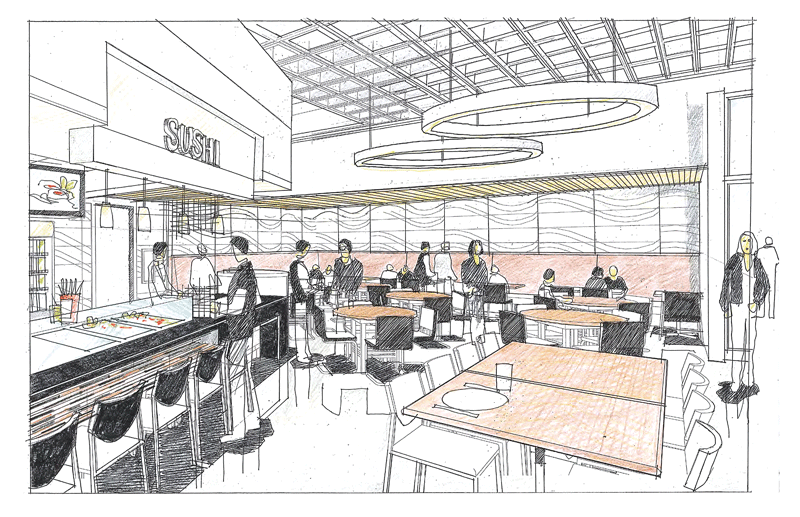

And soon, there will be even more for such delegations to see. Indeed, work is proceeding on an extensive, $19 million renovation of the former Blue Wall cafe and adjacent space in the Campus Center into a 33,000-square-foot eatery that will sit more than 800 people (more on it later).

The emergence of UMass Dining is an important development for the university on a number of levels, said Toong, citing everything from the national exposure it brings to the revenue generated for the school; from help in bringing top students to Amherst to improved quality of life for all those on campus.

“We firmly believe that a strong dining program can do a lot of things for a school,” he explained. “It can certainly help a great university like UMass attract top students, and we also contribute to the financial well-being of the university.”

For this issue, BusinessWest goes behind the scenes at UMass Dining to get a taste — literally and figuratively — of how this turnaround has been accomplished and what it means for the university and its students.

Food for Thought

They’re known as ‘Baby Berk 1’ and ‘Baby Berk 2.’

These are the two colorfully painted food trucks operated by UMass Dining and now seen at various locations around the campus. They were given those names, said Garett DiStefano, director of Residential Dining at the university, because they’re essentially scaled-down, mobile versions of the Berkshire Dining Commons, also in Southwest, where they are parked when not in use, which means only for a few hours a day.

Garett DiStefano, seen in the renovated Hampshire Dining Commons, says UMass Dining places a strong emphasis on the “customization of food.”

“The food trucks allow us to have the ability to go around campus any time of day, any location, no matter what the event is, and serve students,” he said, adding that the vehicles got a workout over commencement weekend earlier this month, serving more than 5,000 customers.

They’re also just one of the many imaginative innovations and programs that have marked what would have to be called the ‘Ken Toong era’ for UMass Dining.

It began in the summer of 1998 when Toong, then working for Marriott International in Canada, saw a want ad that caught his attention. UMass Amherst was looking for an executive director of Dining Services.

The position appealed to him on a number of levels, but especially because it offered him an opportunity to put the many lessons in effective customer service he’d learned from Marriott in an intriguing and challenging setting — higher education, and, specifically, a UMass campus that was somewhat behind the times when it came to food services, as evidenced by the fact that perhaps a third of the student body was enrolled in a meal plan.

“I would say that they were not very customer-focused,” said Toong of the operation he joined, adding, in diplomatic terms, that the staff was in many ways talented, but not particularly well-trained or current with best practices of the day.

So he set about changing that equation.

His business plan, if one were to label it that, called for sweeping changes in what foods were served and how, with a much greater emphasis on both the customer and his or her experience.

The food trucks at UMass Amherst, Baby Berks I and 2, enable UMass Dining to take its service to another level.

He certainly didn’t envision that, a decade later, the school would be serving more than 3,000 pieces a day.

“We serve more sushi than anyone else in the country, and this is New England, not Southern Calif.,” he said. “At first, I wasn’t sure we could serve sushi here; now, if we took it off the menu, I think there would protests across campus.”

But there is much more to this story than raw fish and rice.

Indeed, Toong and his staff have taken UMass Dining in a number of new and intriguing directions — from new eateries on campus, such as a facility in the main library affectionately named Procrastination Station, to those aforementioned food trucks; from a host of educational initiatives on healthy eating to the UMass Permaculture Initiative, a cutting-edge sustainability program that has received accolades from the White House.

As they talked about all that, Toong and DiStefano referenced what they called the ‘Millennial diner,’ their term for today’s college student — a very demanding customer indeed.

“They want everything — they want food that tastes good and is good for them,” Toong said of this constituency, which also demands sustainability and the support of local farmers and manufacturers. “We serve the same customers several times a day, so the food has to be good, and it has to be a good experience; otherwise they get bored. That’s why we change the menu all the time; we’re like casino dining, but without the games.”

Power Lunch

Meeting the many wants, needs, and demands of the Millennial diner is the unofficial mission of UMass Dining, the largest campus food service, by revenue, in the country.

This is a multi-faceted operation that includes four dining commons — Hampshire, Worcester, Franklin, and Berkshire (they’re named after Western and Central Mass. counties), as well as 20 retail locations, including the Baby Berks, a bake shop operating in the Hampden Dining Commons, and other facilities.

Together, these eateries serve roughly 45,000 meals a day, or 5.5 million a year, said DiStefano, adding that what is served, when, and how are all functions of the operation’s hard focus on customer service and making necessary adjustments to reflect the calendar and specific needs.

The food trucks, for example, operate from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., and will park at various locations across campus. Meanwhile, dining commons, which years ago closed by early evening are now staying open much later.

“Between 9 p.m. and midnight, we’ll feed 3,000 students a day in the dining commons,” said DiStefano, adding that many customers are averaging what amounts to four square meals a day, not three. “What we try to do is keep pace with what’s going on in the campus community and adjust accordingly.”

During final exams and the reading period that preceded them earlier this month, hours of operation in the dining commons were extended to 2 a.m., while other operations, such as Procrastination Station, were open 24 hours a day.

Meanwhile, UMass Dining employees will generally eat in the campus facilities every day, he went on, adding that this is the best way to see what’s going on and gauge student opinion.

“We have to see things from a student point of view,” he told BusinessWest. “If you’re not looking at what the customer sees every day, you’re going to miss some things.”

Overall, UMass Dining owes its success to successful relationship-building efforts, said Toong, adding that there are many constituencies involved.

This architect’s rendering shows what’s planned for the former Blue Wall café, a 33,000-square-foot eatery that will seat more than 800 people.

In fact, parents can eat for free whenever they visit the university, said Toong, and they can contribute recipes to a cookbook called Taste of Home, now in its fifth edition.

The current volume includes bacon brussels sprouts from the Berson/Krohngold family in Cleveland, mix bean curry from the Bhatt family in Lexington, apple puffed pancakes from the Brady family in Ludlow, and fiddlehead ferns with Hollandaise sauce via the Carlton/Bates family in Turners Falls.

“Some dining operations around the country don’t want to get the parents involved,” said Toong. “We’re just the opposite; we know they’re the ones paying the bills, and we want their input.”

Meanwhile, the university is sharing recipes, best practices, and thoughts about where this industry is headed next with representatives of a number of colleges and universities, said DiStefano, adding that college dining is a very collaborative business sector.

“We’re not competing against Stanford or UC Berkeley or UCLA,” he explained. “So we get to pool information and say, ‘what is UCLA doing that we should be doing?’ and ‘what is UMass doing that UCLA should be doing?’”

On a Grand Scale

They’re called ‘trash fish.’

That’s an affectionate industry term for a range of underutilized species, including hake, blue fish, Acadian red fish, pollack, and dogfish, said DiStefano, adding that the name originates from the fact that fishermen once simply threw these fish away because no one wanted them.

But as traditional staples such as cod and salmon have become overfished, attitudes about these trash fish have changed, and the university is now at the forefront of a movement to create a market for these species by including them in a number of recipes, such as the one for fish tacos. And by doing so, the school is supporting struggling fishermen, diversifying students’ palates, taking the pressure off over-fished species, and further promoting healthy eating.

“This allows us to support fishermen who might otherwise be out of business because there are limits on salmon and Atlantic cod,” DiStefano explained, adding that use of these trash fish is just one example of how the university’s dining service goes about meeting the many facets of its mission statement, everything from sustainability to healthy eating to supporting the local economy.

And that word ‘local’ has a broad definition, said both DiStefano and Toong, noting that the university buys from asparagus growers in Hadley, Angy’s in Westfield (pizza dough), Performance Food Group in Springfield (a $15 million annual contract), a bakery operation in Boston, and the Hadley Sugar Shack, among many others.

“It’s part of our mission to support people who support the economy around us — as we grow, they grow,” said DiStefano. “And when we survey our students, more than 75% of them say buying local is important to them. The word ‘local’ to them means they’re tied to the community, and community is very important to them.”

In addition to buying local, UMass Dining also puts a heavy focus on healthy eating, said Toong, adding that this is both a national trend and a reflection of changing habits — and attitudes — among today’s college students.

In response to this change, UMass Dining has initiated what it calls its ‘stealth health program.’ It covers all the bases, said Toong, from reducing sodium in recipes to serving more fruits and vegetables to providing portion control through a philosophy summed up with the phrase ‘small plates with big flavor.’

“Five years ago, we spent about $1.5 million on produce,” said Toong, using more numbers to get his points across. “This year, we spent close to $3 million.”

All these characteristics of the dining program — from the smaller portions to the diversity of the cuisine to the emphasis on sustainability — are clearly in evidence at Berkshire Dining Commons, which underwent extensive renovations six years ago, and the new Hampshire Dining Commons. Together, they serve the 6,000 people living in Southwest, one of the most densely populated areas in the country.

As he offered BusinessWest a tour of the former, DiStefano started at the so-called Noodle Bowl. “Noodles are hot right now,” he said, adding that this station enables students to pick not only their noodle — there are several options — but also the broth and toppings they want with it.

“This allows the customization of food,” he said, using that term for the first of many times, while noting that almost all the cooking is now done in front of the student, and meals are made to order.

This is true at the nearby vegetarian station, the salad station, an area where students can design their own flatbread pizza, the wok station, the Pasta Pronto station, and an area marked ‘street food.’

“This is the worldwide concept of food — anything that’s small and eaten by hand, like tapas and sliders,” he explained. “It’s all made to order — we’re continuously making small batches of it all day long.”

This is a trayless environment, DiStefano explained, adding that students will take what they need and go back for more if they need to, rather than piling things onto a tray. This concept, another idea that came from students, has enabled the school to reduce food waste by roughly 30%.

The open, oval layout at Berkshire, designed to eliminate lines and bottlenecks, was taken even further in Hampshire, said DiStefano, noting that best practices from dining commons around the country were incorporated into its design and operations.

“The oval design allows students to see everything around them, they can find a seat quickly, and they can engage with chefs behind the line in terms of what they’re cooking,” he explained. “And they can hear, smell, and see what’s being prepared in front of them.

“The oval design also diminishes queues, because you can pick a little bit at each station,” he went, “as opposed to going to one station and lining up and going to another station and lining up.”

Many of these same concepts will be put to use at a facility being built on the site of the Blue Wall, said David Eichstaedt, director of Retail Dining for the university.

He told BusinessWest that a new classroom building now under construction near the Campus Center will bring several thousand students each day to that part of the campus, and larger, more modern, more customer-friendly facilities are needed to serve that population.

The new eatery will include many of the features found in the renovated dining commons, including a bake shop, a host of food stations, and made-to-order foods. The yet-to-be-named facility — students will ultimately make that decision through social media — is scheduled to open this fall.

Lobster Tales

Last Halloween night, UMass Dining served surf and turf for the masses.

The program was called “Just Treats, No Tricks,” said DiStefano, and featured steaks and lobsters — 12,000 of them.

That grand meal is just one of many ways to measure just how far this program has come in a few decades, and how important food service has become for a school that may soon have a rival for its marching band when it comes to national acclaim.

As the chancellor said, “come for the food; stay for the education.”

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]